The Australian Government has a problem. Its aged care regulator, the Aged Care Quality Agency has given 95% of nursing homes a perfect score in meeting quality standards. This means 95% of nursing homes are assessed as providing safe care.

But barely a week goes by without the media uncovering stories of abuse, neglect and poor standards in Australian nursing homes. Often these stories are from facilities which have passed quality checks. Rarely is a facility closed because it is found to be unfit to provide care to its vulnerable residents.

So what should a government do with such a conundrum? Some gauche policy wonks may suggest tightening quality checks to reduce the incidence of a mismatch between the Agency’s assessment of these places and what’s exposed in the media.

Others may nip the problem in the bud by removing quality checks altogether.

And this is exactly what the Australian Government is doing. Minister for Social Services Kevin Andrews this month launched the innocuously titled Aged Care Innovation Hub Trial to reward providers which ‘have consistently demonstrated high levels of care’ with reduced quality checks.

Minister Andrews is delivering on an election commitment to reduce red tape in aged care (announced the day before the election) in response to providers’ wishes to have ‘greater autonomy’.

Ten providers are participating in this Trial, which will be independently evaluated after 12 months. Presumably, if the evaluation is positive, the policy will be rolled out nationally.

Care recipients can look forward to ‘greater consumer engagement’.

In other words, if you live in one of these places and have six bed sores that have been bugging you, your care provider may talk to you about this. You could do this without an Innovation Hub, but hey, they had to say that care recipients could get something.

The Department of Social Services insists that care recipients will be protected by safety nets, including the Charter of Residents Rights and Responsibilities and the Aged Care Complaints Scheme.

The problem is that the Charter is not legally enforceable and few residents know about the Complaints Scheme (one in three according to the Australian National Audit Office).

Even when residents are aware of the Scheme, many don’t complain for fear of retribution. How will the Trial manage this problem when the last thing that providers would want is care recipients complaining?

Care recipients are pretty much being left on their own to engage with their nursing home which has a distinct interest in getting a positive result from this Trial.

This red tape reduction will apply to providers which ‘consistently demonstrate high levels of care’. According to Quality Agency reports most would fit that bill. Since 2006, at least 90% of nursing homes have passed quality checks with full marks. In other words, if this Trial became federal policy, nine in every ten homes could have quality checks reduced or abolished.

At the moment, nursing homes undergo a ‘re-accreditation check’ once every three years, assessing them against all 44 quality standards. This check is announced months in advance because the nursing home has to apply to the Agency to have it done.

All homes have at least one unannounced ‘spot check’ each year. However these checks only review the home against about a quarter of the quality standards.

The only time a nursing home will be assessed against all standards during an unannounced visit is if there are serious concerns about its operations. This happened nine times in 2012/13.

Is it any wonder then that Australia has such a fantastically high pass rate for its nursing homes when quality checks are either announced or recklessly lax?

Quality checks in nursing homes are not an ‘unnecessary administrative burden’ as the Minister described such regulation in his press release announcing the Hub.

They are an important part of any healthcare delivery system, but critical in residential aged care where care recipients are frail, vulnerable, and often cannot speak for themselves. About 75 per cent of Australia’s nursing home population have high care needs, and most of that group have some form of cognitive impairment.

These people are generally not in a position to advocate for better care or their rights. That’s left to family and friends who pay attention to what’s going on. Many don’t have that. But even those who do, often family members are left fighting a system that’s set up to fail them.

This Trial will be conducted in consultation with COTA Australia which is the consumer representative. COTA will work to ‘better engage’ care recipients and presumably play a key role in the evaluation. However, two of COTA’s Board members have direct ties to the aged care industry as a CEO and Director of aged care providers.

Given that providers have a clear interest in a positive result from this Trial, it would be helpful to see how COTA plans to manage any conflict of interest.

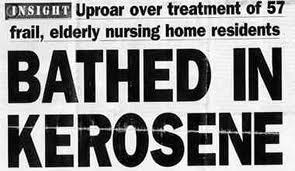

The Trial takes quality checks back to what they were when residents were being given kerosene baths.

Is this what Australians really voted for?

Source: Nursing Home Black Box (A blog about the state of nursing homes in Australia by Combined Pensioners & Superannuants Association)